I had an interesting discussion today with a colleague about looking at high growth companies, and we both approached the question with two distinctly different perspectives on what makes a valuable company from an acquisition point of view. Fundamentally our discussion still focused around a question that is also relevant to the new product view for any venture – when is the real value and ROI generated in regards to cash flow?

With my IP Strategy background I am naturally drawn to the IP and Patent aspect of a venture, so naturally I extended this question to how can an IP Manager or leader in an organization ensure an IP portfolio support a positive cash flow position.

One view was a ‘high velocity cash’ position, where the value of an acquisition is fully linked to the amount of ROI it immediately generates in positive cash flow, which may or may not include the influence of IP. If IP existed cash flow would be via licensing, royalty rates, increased pricing due to brand, etc. The alternate view was ‘high growth IP’ backed position, where the value of the acquisition was based on the value of the tangibles, as well as the future market protection the intangibles covers – including the long tail opportunity seen in future licensing both inside and outside of the specific venture’s industry. Removing the actual ROI seen, the main differentiator was the time of positive cash flow with the ‘high velocity position’ heavily front loaded in comparison.

I don’t necessarily think either perspective is incorrect, as the value perceived is different depending on which criteria you use for acquisition. However the discussion does raise a broader point for Startups, SME’s and even multi-nationals: A venture’s business model of IP has to incorporate multiple views and timelines to be marked as successful, as having a singular model that moves from one binary state to the next will give the appearance to fluctuate in value strictly based on who is looking at it. There needs to be a more balanced perspective when looking at the real value IP brings to a business.

IP programs that align with the business should have many stakeholders, for example, Inventors, CEO’s, Product & Market Managers, Finance, etc., and each with their own measure of success of the actual impact of IP in the venture. Again, it is not that each view is wrong but rather HOW each views it through the priorities they have that an IP Manager or leader needs to take into account.

In practice, successfully implemented IP programs are able to balance the functional needs by providing a strategy where value of IP in a business can be seen from each perspective. Without this, there is now way to talk about IP in the boardroom, either at the strategic or execution side of a discussion.

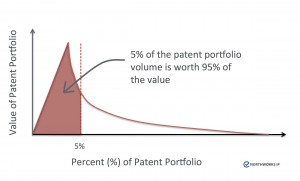

Take, for example, an average patent portfolio of a venture: Generally there will be a long tail distribution of the value, where a few patents are worth the majority of the portfolio as a high value, and the remaining abundance of patents may have been provided to protect a product offering but realistically have low or no value for generating cash flow. The ‘high velocity cash’ perspectives (perhaps as a Finance or Operations view) tend to view the value of a portfolio of what can be monetized or leveraged in the moment to influence the immediate cash position. Product Mangers or Inventors tend to view the value of “IP success” as what breadth scope is protects products, and not always with the specific concern of immediate cash returns from IP. CEO’s and those in the boardroom focus on both short and long term views, placing value on the venture or product if the current quarter as well as several into the future.

To make it more complex, as time moves on both portfolio scope and market needs will independently shift and unless the portfolio grows to take this into account the relevancy and ROI of the portfolio will be impacted. Granted, given the length of patent terms the shift may be slow, but for fast moving consumer markets and areas where disruptive innovation is moving the direction of an industry it will happen.

With that in mind, and coming back to the original question: What perspective is the best when looking at an acquisition, high-velocity cash or high growth IP potential? And, taking this to the SME and Startup venture level, what perspective is best when looking at developing a new product, because after all a venture with a new product idea is essentially “acquiring” the product through its own development efforts. Should an investor or CEO focus on the high-velocity cash opportunity or the long game of an IP based option?

The answer in my view is either, or the combination of both that that strikes the right balance for the stakeholders in the venture. In other words IP Mangers need to be able to create an IP portfolio that has portions which are able to be monetized in the short term – the “high-velocity” cash position – as well as build a portfolio that can be used in longer term protection strategies – the “high growth” IP backed position. It sounds incredibly simple but in practice the actual balance of creating a portfolio mix that takes into account items such as breadth of coverage vs. depth of coverage, timeline to grant vs. market trends for product releases/end-of-life, etc. is incredibly complex and may take several years to build. To make matters more difficult, unless an IP Manager or Chief IP Officer can successfully talk to this at all levels of the organization to generate support which will help create such a balanced portfolio- from Inventors to the CEO in a boardroom setting – there will always be other strategic or operational items that dominate in the discussion of “What makes this venture / product valuable?”.