The First Mover Advantage of IP: Patents vs. Velocity

Startups and Fortune 100 companies take note: Jeff Bezos is positioning Amazon at the future center all of web commerce. And he is planning reaches at least 7 years into the future. Earlier this year Amazon said it was experimenting with delivery by drones, dubbed Amazon Prime Air, and details were found on anticipatory shipping before an order is even placed. Despite this being “new” news for the consumer world Amazon actually filed a patent on anticipatory application in 2012, claiming priority to 2004. So yes, the recently granted US Patent 8,615,473 which covers order fulfillment and shipment of shipping packages before an order has occurred, was contemplated and filed for a patent 10 years ago.

In 2004, Amazon started contemplating filing patents ‘predictive shipping’. 2014 was the year the patent granted and the tech community picked up on their future plans.

This type of advance patent filings seems the norm for Amazon, with another example as the famous “One-click patent” on a method and system for placing an order. Merits of US Patent 5,960,411 patent aside, which as been re-issues, affirmed or denied at various times by US, Canadian, and European courts, it should be noted since it was filed in 1997 it has been cited over 1670 times by other patents. It is, by the definition of patent statistics used in academia, considered a highly valuable patent. Amazon has used the ‘411 patent in litigation with Barnes and Noble, who arbitrarily added more clicks to get around the patent, and has actively licensed it to companies such as Apple as far back as 2000.

But not all companies have had the fortune to plan and execute IP in this manner. Rapid growth combined with IP as a non-core strategic asset has put a few notable companies on the offensive. Both Linked-in and Twitter had under 10 granted patents by the time the IPOs were announced, and for at least Twitter this was seen as a risk to some investors when compared to the volume by their rivals Facebook. Pre-IPO negotiations by IBM against Twitter resulted in the vast majority of Twitter’s 1800+ portfolios coming mainly from IBM. Facebook’s IP growth has been through acquisition, spending at least $1.6B on acquisitions between IBM, and AOL & Microsoft since 2012.

Google has maintained a more stable growth of IP through filings and of late a $15B combined purchase of IP and Technology has given it key acquisitions such as Nest and Motorola. Last check gave Google at over 32,000 active patents, their exponential growth of IP not really beginning until after 2001. This is a far cry from 1994 where at technology inception only four filings were done. A cursory review of Google’s early patents gives the impression they were filings based on technology in production. Yahoo’s 5000+ active filings tell the same story of starting small with only 1 filing in their year of inception (1994), 9 in year 2 around web pages, but the filing volume growing exponentially by year 3 of operation.

For startups and other high growth companies this outlines two generic paths than an IP plan can evolve from:

- IP Acquisition After Growth, as seen by Twitter, Facebook, and Linked-in.

- IP + Technology Strategy, which later moves from organic to include acquisition growth as seen by Google, Yahoo, and Amazon.

Ultimately for market leaders the paths do end up together were IP becomes a critical element of their competitive position. For example, Yahoo’s high growth rate gave it a deep pool to use as a tool against both Google and Facebook when the filed to go public. However the Facebook offensive position was not such a successful tactic as Facebook used the acquisition of the IBM and Philips patents to countersue Yahoo.

Companies where the high velocity growth of a customer base is key, such as Facebook, Linked-in, and Twitter, are mainly adopting the IP Acquisition After Growth path. For the ventures where velocity trumps IP, as growth occurs planning for future cash to deal with the problem is a viable solution.

However focusing on the path of IP + Technology Strategy gives some valuable lessons for startups to consider. Consider the organic portfolio growth rate of Amazon, Google, and Yahoo of the, or filings by the original company and not those added through acquisition: comparing filings since 1994 indicates their actual patent growth rate varies but the business approach is the same when looking at the overall portfolio to date – small to moderate growth in the initial years of the company and a high exponential after 2002 for all involved. A more detailed view of the years prior to 2002 shows similar corporate trend of the startup years 1 and 2 having less than 5 filings, and a mini-exponential trend starting at years 3 of operation and beyond where patent filings per year jump above 30 filings per year for some ventures. Google is the notable exception, taking until its 6th year of operation to rapidly increase the filings.

While the filing trends are relatively similar a key difference can be seen in the portfolio content, specifically with Amazon. As a reference point by the time the one-cick ‘411 patent was filed in 1997 Amazon had $148M in revenue and 1.5 million customers, after experiencing rapid expansion during its launch only 2 years earlier. Even at Amazon’s inception in 1995, the first year of operation saw several patents by Jeff Bezos and his team filed around topics such as secure communications of credit cards over non-secure networks. Looking forward into Amazon’s growth we can see the two IP Strategy paths are coming together: with Amazon how having over 4400 patents their strategy stepped up again in 2012 when they added a Patent Acquisition & Investment leader to their team. Through this we can see how Amazon is continually building IP into their DNA, making it an integral part of the corporate strategy.

The important lesson in the first few years Amazon’s patent position is rooted around Jeff Bezos long term plan on owning the web. As outlined in the Steven Levy article in Wired Magazine (2011), Bezos highlights an important point for startups and large ventures to heed, which was present in the shareholder letter he penned back in 1997.

“But if you’re willing to invest on a seven-year time horizon, you’re now competing against a fraction of those people, because very few companies are willing to do that. Just by lengthening the time horizon, you can engage in endeavors that you could never otherwise pursue. At Amazon we like things to work in five to seven years. We’re willing to plant seeds, let them grow—and we’re very stubborn.” – Jeff Bezos

Looking at the long term Bezos pushes Amazon to work in the 5 to 7-year horizon. More impressively he has had the patience to align his patent filings in the same way, and is still doing so if we use the proxy of “predictive shipping” patents filed in 2004 that was recently uncovered as a future Amazon service.

So what lesson can startups take from this?

For startups and other high growth ventures that choose to focus on the IP + Technology Strategy path of IP evolution this provides some guidance on how successful portfolios for pure software based organizations started. A take-away action for CEO’s is to have a discussion with their board and leadership team about their IP strategy plan. The conversation can be simplified down the question about portfolio allocation and coverage.

Key Question: Does our IP strategy allocate protection for today, tomorrow, and the future’s competitive markets?

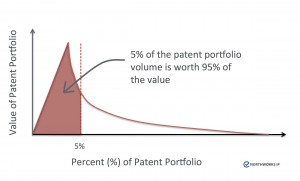

Allocating a portion of the portfolios future technology position at company inception, even if the filing volume is fairly low, positions the venture’s portfolio well ahead of the evolving marketplace. This approach also mitigates the risk that exists in the technology industry where software releases are growing 2-3x faster than the patent office can pace with. In short, it provides support for the “quality” aspect to a portfolio even if the volume is small in the first few years.

As growth happens and the marketplace becomes more saturated with sustaining technology, the ventures will have already identified and filed for protection for new disruptive technologies and processes that will become a fundamental piece of the market. The result of aligning a 7-year plan with IP is a granted portfolio that is positioned to be relevant in the 10+ year timeline.

For the pace of filing in the first years of a software based startup, the data shows a modest number of filings in the first 2 years of operation, and year 3 of operation was where the high growth of filings occurred. However considering the increased pace of technology growth now compared to the 1998-2000 time frame it is not unreasonable to consider 2 years of operation now happening in 6 months of development. A rapid decrease in the barriers for new ventures to start and launch means the IP Strategy must adjust for this new environment.

Followup Question: Are the patent filings focused on pure technical coverage for today’s technical solutions, or is there room in the filings to reposition the IP as the market evolves by covering solutions to our future disruptive technology?

Over time markets evolve and technology advancements catch up with customer pain points. What historically took years of development can now be created and released on a global scale in months, yet the 20 year life of a patent still remains the same. With this 20 years of life, spending time answering these questions and positioning an early portfolio could be the difference between the venture paying out in the face of competitive IP pressure or reaping the financial and market benefits as patent ownership becomes a critical success factor in the industry.